The operationalization of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019 is a blow to the Indian constitutional values of equality and religious non-discrimination and is inconsistent and incompatible with India’s international human rights obligations, said Amnesty International today.

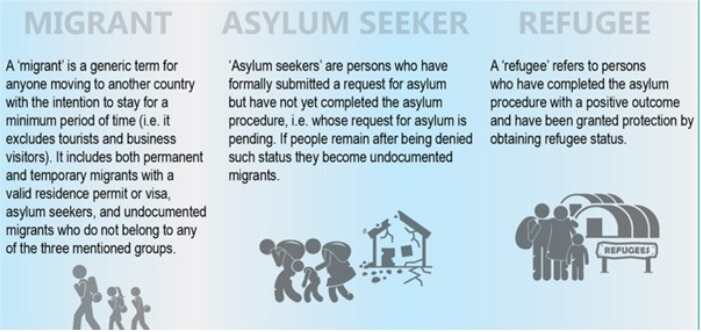

The Citizenship Amendment Act will benefit thousands of Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan who entered India before December 31, 2014, and seek citizenship of India. This group of people has been living in India illegally or on long-term visas.

What is the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India?

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) aims to protect individuals who have sought refuge in India due to religious persecution. It offers them a shield against illegal migration proceedings. To be eligible for citizenship, applicants must have entered India on or before December 31, 2014. Currently, Indian Citizenship is granted to those who were born in India or who have lived in the country for at least 11 years.

The CAA also includes a provision for the cancellation of Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) registration if the OCI cardholder violates any provision of the Citizenship Amendment Act or any other applicable Law.

What information must the intended beneficiaries of the CAA provide?

The Citizenship Amendment Act aims to give citizenship to the target group of migrants even if they do not have valid travel documents as mandated in The Citizenship Amendment Act, of 1955. The Citizenship Amendment Act presumes that members of these communities who entered India faced religious persecution in these countries. The law has also cut the period of citizenship by naturalization from 11 years to five.

Under the Citizenship Amendment Act Rules, immigrants from these countries are only supposed to prove the country of their origin, their religion, the date of their entry into India, and the knowledge of an Indian language to apply for Indian citizenship.

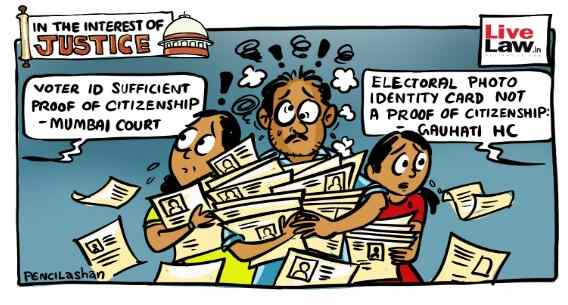

What proof is required to establish the country of origin under CAA?

The rules have been relaxed very significantly. The earlier essential requirement of a valid passport issued by Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Afghanistan, along with a copy of a valid Residential Permit from India, has been virtually done away with.

According to the Citizenship Amendment Act Rules, a birth or educational institution certificate, “Identity Document of any kind”, “Any License or Certificate”, “Land of tenancy records”, or “Any other document” issued by these countries, that proves the applicant was their citizen, would serve as proof of citizenship of these countries.

How will the date of entry into India be established?

These include a valid visa or residential permit issued by the Foreigners’ Regional Registration Office (FRRO); a slip issued by census enumerators in India; a driving license, Aadhaar, ration card, or any letter issued by the government or a court; an Indian birth certificate; land or tenancy records; registered rent agreement; PAN card issuance document, or a document issued by the central or a state government, PSU, or bank; certificate issued by an elected member of any rural or urban body or officer thereof, or a revenue officer; a post office account; an insurance policy; utility bills; court or tribunal records; EPF documents; school leaving certificate or academic certificate; a municipality trade license; or a marriage certificate.

Who will be in charge of processing the applications for citizenship?

Opposition-ruled states including Kerala and West Bengal have said they will not implement the Citizenship Amendment Act. Under the Rules, however, the Centre has tweaked the process of granting citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from the three countries so that states will have little say in the matter.

Thus, while citizenship applications were earlier made to the district collector — who is under the administrative control of the state government — the new Rules provide for an Empowered Committee and a District Level Committee (DLC), to be instituted by the Centre, to receive and process the applications, which are to be submitted electronically.

The DLC shall consist of the District Informatics Officer or District Informatics Assistant of the concerned district, and a nominee of the central government. The two invitees to the committee will be a representative of the district collector’s office not below the rank of Naib Tehsildar or equivalent, and the jurisdictional station master of the Railways (subject to availability).

Is this the first time the government has moved to address the plight of these refugees?

No. The first steps in this direction were taken back in 2002 when the state of Rajasthan requested then Deputy Prime Minister L K Advani to help resolve the difficulties faced by Pakistani Hindus trying to procure Indian visas and citizenship.

As a result, in February 2004, the government of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee amended The Citizenship Rules to give district magistrates of certain border districts in Rajasthan and Gujarat the power to grant LTVs and citizenship to such migrants.

Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan were eligible under this policy, apart from Pakistani women who were married to Indian nationals and were staying in India; widowed or divorced Indian women who were married to Pakistanis; and “cases involving extreme compassion”.

Grant of LTVs was also considered in the case of originally-Indian Muslim men who went to Pakistan after Partition leaving behind family in India, and returned on valid Pakistani passports and settled in Kerala.

In December 2014, the first Narendra Modi government issued a notification allowing the grant of citizenship to Hindu, Sikh, Christian, and Buddhist migrants from Pakistan. Jains and Parsis were not included in this relaxation.

Conclusion

In 2015 and 2016, the government amended The Passport (Entry into India) Rules and The Foreigners Order exempting Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Christians from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh from the process of law in case they entered India without a passport or visa.

Finally, in 2018, a year before Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, the government issued a notification that made these communities eligible for LTVs if they sought Indian citizenship. A range of benefits was extended to them — they could get a private job, start a business, admit their children to school, move freely within the state, open a bank account, buy a house, and get a driving license, PAN, and Aadhaar.

-RIYA SINGH

MUST READ: GEOPOLITICAL INTERPLAY: A CLOSER LOOK AT INDIA-SRI LANKA RELATIONS